How to Not Fail the Chemistry IA

- emadelinelane

- Apr 7, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2024

Chem IA

Welcome, chemists! Presumably, you are in the beginning stages of creating your Chem IA, the piece of your exam that will be graded by your teacher and moderated by IB. This generally takes the form of a student-devised experiment, which you will conduct* and analyze the results of under the loose guidance of your teacher.

In my experience, this piece of the exam was the hardest, mostly because the work-to-result ratio of paper exams is much more secure; if you study a lot, you'll do well on the paper exams. However, sometimes practical experiments fail or go awry, no matter how much prep work and research you do. On the flip side, the IA is super fun and by far the most personalizable part of the class! Within bounds, you will most likely be allowed to study any topic that interests you and delve deeper into your passions!

A few important notes for this article: 1) my experiences with the Chem IA are based on a rubric that will be changing this coming year (M25) as is part of a standard IB process where each subject’s assessments and procedures get a refresh every 7 years. In theory, most of the advice in this article will still be relevant to the IA process, but take things with a grain of salt and defer to your teachers if their instructions don’t align with my advice. 2) Full disclosure: I received a 16/24 on my Chem IA, one mark below a 6. This was my lowest IA score, and I therefore would advise that you use other resources in addition to my blog to help you be successful, depending on your target score for the IA. Alright, sorry for all the introduction. Onto the tips!

Have an Expected Result

If it’s at all avoidable, do not choose an experiment where you don’t know what your results should be under ideal conditions. Especially for those students who are strong in the STEM subjects, it can certainly be tempting to want to do something super unique and groundbreaking. However, IB doesn't want or expect you to discover a new gas law or a cure for cancer. They just want to see that you understand basic scientific procedure, the application of classroom concepts, and an ability to reflect back and evaluate your processes. That third one, evaluation, is super important, but it's also nearly impossible to achieve without a pre-established frame of reference.

A good reference point might be a lab report from an iteration of your planned experiment. If you use this, make sure to cite the report in your IA. You don’t need to have that, though, as long as you can use sound scientific reasoning to deduce a predicted result. In my case, that looked like plugging textbook values into a couple reliable formulas to find my expected heat output. If you are planning to use the second method, it’s a good idea to run your process by your supervisor, whether that's through a simple conversation or just by making sure it is fully fleshed out when you turn in your initial draft for feedback.

On the subject of using reference materials, some people will derive their procedure from the lab reports mentioned above, but others (myself included) develop their own procedures. This might be because there are no readily accessible lab reports or simply because you wanted to get creative with your procedure. This is totally fine, as long as you have a logical expected result and you clear your procedure with your supervisor ahead of time. Additionally, you should state explicitly in your paper that you have not used any pre-existing materials to create your procedure. This isn’t "required" per se, but when it comes to IB assessments, its always best to cover your bases so as not to be wrongfully accused of plagiarism.

Approaches to Uncertainty

Uncertainty is one of the most confusing bits of the Chem IA in my opinion. Your methodology for finding and discussing it will depend a lot on the nature of your experiment. As of writing this, I do not have a breakdown of exactly where I lost points on my IA, so I can't be absolutely sure my uncertainty procedure was acceptable. However, I modelled it off of an IA that received a 7 (link) and my teacher approved it during our feedback session, so I’ll share it here.

Essentially, what I did was to log every piece of instrumentation and its uncertainty. Then, you divide the uncertainty value by the smallest measurement you recorded with each device. This will net you a percentage of uncertainty for each device that can then be added together. See chart below for clarity.

This method accounts for the maximum possible error in your experiment by taking the smallest measurement for calculations. Think of it like this: 0.1 g uncertainty is going to make a much bigger difference if you have 1g of substance versus 10g because the ratio of uncertainty to measurement is much higher. By using this method, you are giving yourself the most wiggle room in accuracy.

This might not work for every experiment. In fact, I highly recommend speaking with your supervisor if you are at all unsure if it would apply. There are several other processes out there, ranging from doing this kind of calculation for each individual data point and averaging to very complex mathematical work that my humanities brain doesn’t really understand. Whatever works for you. Just make sure to include your uncertainty calculations in your paper, both once in the paper to demonstrate your process and, if applicable, all other data points in the appendix.

If at First You Don’t Succeed

I’m not a super STEM-oriented person, and as stated previously, I found the IA challenging. I ran my experiment 3 separate times- once because my materials sucked, once because my design sucked, and the final time, it worked. I also know of a lot of other students whose experiments failed at first or even continued to fail. It’s gonna be okay.

If something is going wrong, the first thing to do is to take a look at your materials. Some chemicals can become inactive over time, or perhaps they are contaminated or even mislabeled. Try doing a “proof of concept” run before setting up your full experiment to determine if your materials are behaving the way they are supposed to. If not, don’t immediately throw the towel in. Do a little bit of research to see if you can find a possible reason why. In my case, I discovered that my reactant could absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide and become a different, less reactive compound. After acquiring fresh materials, the experiment worked as planned.

Next, evaluate your experiment design. Are you using all the correct materials in the correct proportions? The right tools/technology? Do you know what you’re looking for? If the answer to all of these questions is “yes,” it may be time to seek some help from your supervisor, a peer or the Internet. Some supervisors will encourage independence more than others, and you may have to do some problem-solving on your own or with the help of other students, but typically if you’re really in a pickle, your supervisor will point you in the right direction.

Generally, I wouldn’t advise jumping ship on an idea unless you’re absolutely certain it’s not going to work, because finding another topic, attaining a solid understanding of the procedure, getting it re-approved and re-designing the experiment is a decent amount of work. However, try to make sure you're not being stubborn and sticking with an idea that is clearly not working, especially if you’re in a time crunch. As a wise teacher of mine once said, "if the horse dies, dismount."

Plan Ahead

What the header says. Make sure you know ahead of time exactly how you’re going to compute your data and confirm that your process makes sense. Know the methodology of your experiment by heart so that you’re prepared when you get lab time. Have a plan for disposing waste materials that your supervisor has approved.

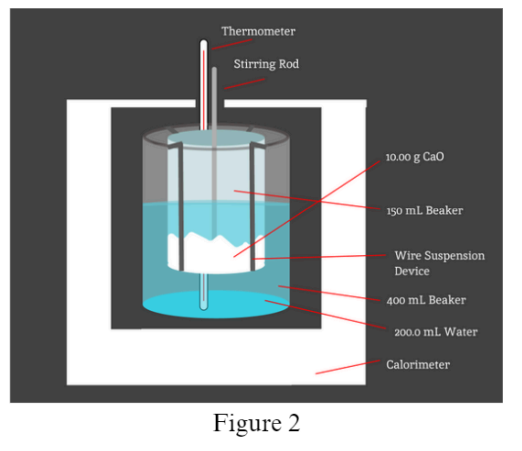

The second time I had to redo my experiment was entirely my own fault. I hadn’t given myself a constant substance to measure heat change in; I just stuck the thermometer straight into the reaction. The problem was that a reaction doesn't have a singular specific heat capacity or mass because it’s changing rapidly from reactants with certain properties to products with different ones. So I had to redesign my experiment using a water bath as a constant substance. If I had thought through how I was planning to process my data, I would have realized way sooner that my initial design was not good. Long story short: work through your process mentally before you do it.

Formalities

Almost done! Just a couple assorted pieces of advice regarding the writing of the paper:

Make sure to include very explicit personal engagement. It’s only 2 points on the rubric, but those can make a big difference in your score. Talk about how you got your idea and try to include something related to your personal life.

Include diagrams and charts wherever appropriate. It gives your paper a more professional feel and, if you have a complex or unconventional setup, it can help the graders understand exactly what you did or why you did it.

If there aren’t any pre-existing diagrams of your setup, you can make one using a graphic design software (I used Figma). You can also use photos of your setup, although in my personal opinion diagrams are cleaner and easier to label.

Technically, there aren’t a lot of regulations on the technical format of the IA, so some people make their font size or spacing super small or super big. Don’t do that. Size 12 Times New Roman font, double or 1.5 spaced is perfectly acceptable. If you feel like you need more space, there’s a chance you legitimately do. There’s also a chance that you’re not being concise enough, or that you bit off slightly more than you could chew. Once again, communicate with your supervisor and take their advice.

Good luck with your Chem IA! Remember to follow proper safety protocol, record everything and also, try to have fun with it. As much as it can be a stressful process, it’s also a unique opportunity that most high school students don’t get. Try to enjoy it! For those wanting a reference, you can read my full IA here.

*There is something called a database experiment that is an alternative to a student performing the experiment themselves, but in my program it was highly uncommon and I am not a good person to advise that sort of IA. If this interests you, I recommend looking at some examples and speaking with your supervisor to determine if this is a good option for you.

Comments